Urban River Worship

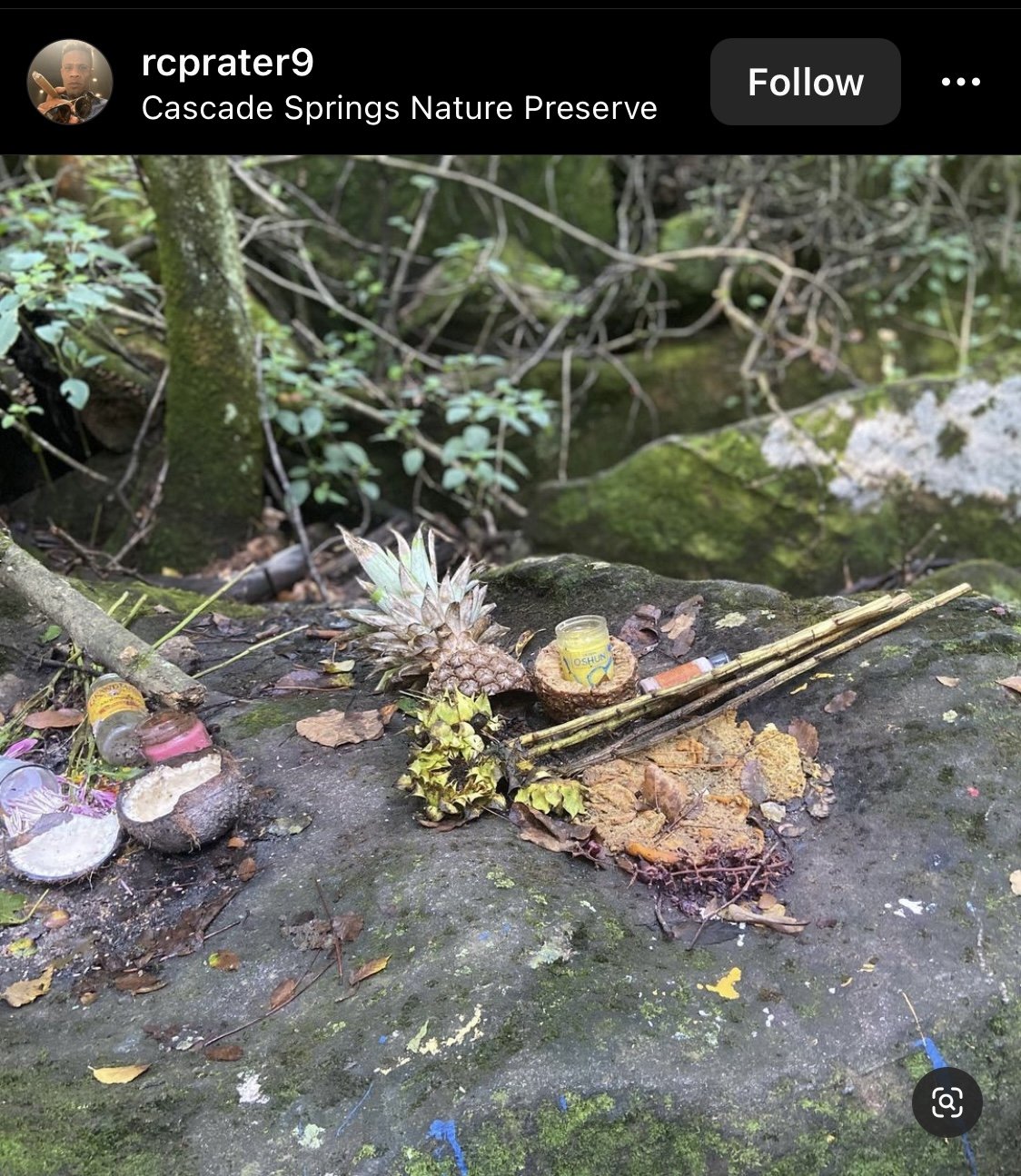

Osun Festival 2021 on the Yellow River. Photo by Tabia Lisenbee-Parker, courtesy of Yeye’s Botanica.

On one of the hottest days of the summer, I took a busload of state agency employees on a tour of the Flint headwaters around the airport. Even though I’ve led this tour dozens of times, it never gets old. The river is always surprising. I see something completely new in every season and I hear new stories and learn new information from every group.

On Willingham Drive in East Point, just as I was talking about the history of Junglefoot and Neriah Baptist Church, I nearly stepped on the carcass of a raccoon. I’m not that good at identifying bones, but the striped tail was unmistakable. I carefully gathered the skull and added it to my bag of litter. What a find!

Unfortunately, it’s not unusual to see dumping along the river, so I wasn’t surprised to discover watermelon wedges simmering under the Forest Parkway Bridge. The red fruit was nearly gone, the sliced and splattered rinds scraped clean. I remembered the raccoon that we saw there a month earlier on a tour with Clayton State University faculty.

(That day, when three Delta Air Lines employees tromped down to the water behind us, I thought we were about to hear about a fuel spill. Instead, they released a raccoon they had trapped in a garbage can. That lucky critter is probably enjoying summer by the river now, dining on tossed watermelon.)

As I stepped closer to the rinds, I saw sliced oranges and whole okra mixed in the river stones. Suddenly, this looked more exciting to me than a liberated raccoon.

The oranges reminded me of offerings to Oshun, the Yoruba river goddess, that you see scattered around Utoy Creek at Cascade Springs. I’ve read about how sunflowers and fruit, honey and wine are poured out by worshippers to welcome the goddess, but I’ve never seen anything like that near the headwaters of the Flint.

It filled me with hope to think that river worship might be making a comeback in Clayton County, at a site that has been overlooked and degraded for so many years. Could this be the result of the signs the county installed on the bridge, publicly naming it a river? Incorporating the Flint into this cultural tradition seemed like a step toward reclaiming the river.

Was there a Yoruba community in Clayton County welcoming Oshun on the Flint? Was that too optimistic?

Yeye’s Botanica, a “one stop spiritual supply store” has a location on Tara Boulevard, only a mile from the Flint River. You can buy incense, gems, ritual candles, cowrie shells, teas, and sage for any purpose, but I stopped by to learn more about Ifa and the orishas. Lucky for me, Omi Segun, an Ifa practitioner, was working that day and generous enough to educate me.

I told her what I saw on the banks of the Flint headwaters and she was skeptical.

“Usually we go someplace really beautiful, like the Yellow River.”

I started to defend the scrappy allure of the place, but she had a point. It’s a river more known for fuel spills and flooding than natural beauty.

“It’s the okra that’s throwing me,” she laughed. Orange segments, sunflowers, kola nuts were typical offerings. Not okra.

I went back to Instagram to see if I had imagined the offerings at Cascade Springs.

Was it an offering? Or was it trash?

Mattresses, pallets, and tires pile up downstream in hidden bends of the Flint River. People dump astonishing stuff in rivers everywhere, but this busy bridge by the airport is not a very practical place to pull over and toss picnic trash.

We talked about how fruit offerings are like the opposite of litter. Something valuable and sweet, selected to benefit the landscape, released with intention and love. The possum and turtle’s delight, rinsed away in one rain shower.

“There’s no way to know for sure who did it,” said Omi. “There are small, private groups spread out all over Atlanta. Ifa requires a lot of driving.”

Though not a direct answer to the mystery, this comment made me think about our bus tours, and what we are doing on these pilgrimages to “find the Flint.” Sacrificing time and resources to observe and appreciate the river—it’s made me the kind of person who collects raccoon skulls.

If I told you that a practice over many years enhances the ability to observe and exercise wonder and gratitude, what is that but a form of worship?

Near Bainbridge, ca. 1910. Baptizing in the Flint River. Vanishing Georgia Collection, Georgia Archives, University System of Georgia.